WW1 recruitment posters analysis, utility and curriculum development

I am currently marking 3 sets' worth of tests for Year 9, which my school did this week for all subjects and all year groups 7-12. While I have a big concern about the efficacy of this as a process (Year 7 English is just not the same as Year 12 A Level Chemistry and should not be treated in the same way, for example) it got me thinking further about the way I have been approaching source analysis across the curriculum and the year groups I teach.

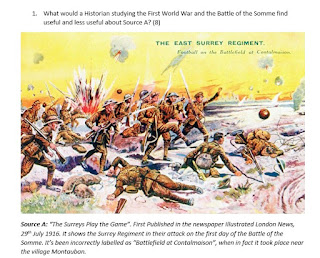

I set this as a source analysis question at the end of a unit on the Western Front, with a focus on Verdun, the Somme and tank development. We had spent time analysing sources in different ways (what they can tell us about the past, the views they have, comparison, usefulness, reliability etc)

Although I appreciate the wording could be different, I chose this source because I felt there was a lot of potential in it and details which students could unpack. There were some good answers from good students, but only a few managed to get the top mark overall (addressing both the "useful", and "less useful", combining content with context and addressing the purpose of the source). Most seemed to explain the content of the source and make some effective points about it not being accurate. Utility for a historian was somewhat of an after-thought.

When designing the mark scheme I was conscious to avoid the very prescriptive demands of a mark-scheme in the OCR History B manner I had been teaching until about 2017:

Looking at this now, it does seem crazy that we thought we could teach students to answer this sort of question without spending time getting students to fully appreciate the job of the historian (I also found this sort of mark scheme very unhelpful for teaching and learning purposes, but that is a blog for another day).

However, source analysis is an area I recognise needs a very clear focus in the curriculum. I had initially thought of it as an exercise in finding the correct choice of words to hit a mark scheme (thanks OCR History B!), and that merely by practicing the questions we would improve. In other words, merely by studying some history, students would be better at analysing sources for an exam.

[Perhaps an analogy might be a sports person learning how penalty kicks are done by watching videos of them without actually doing any in practice before the match]

This worry has been percolating in the background for a while, and I have been wondering what I was missing. This has spurred me on to start thinking about curriculum development more deeply than I had managed in the past.

The ever-excellent Christine Counsell has some very useful things to say about curriculum development for the Historical Association and the Chartered College of Teaching (for example see this article in Impact). Others, like Ford in TH 157, have written about the process of analysing sources within a curriculum; clearly it is a skill which is a challenge, but should be integrated carefully into curriculum development, especially when designing enquiries to structure a unit. Here's something I put together while thinking my way through skills development for a curriculum:

In order to more fully understand the questions and to be able to really comprehend the job of a historian, some of the source-analysis tasks I have relied upon in the past will need to be re-tooled to get the students thinking about the nature of the historian's job, rather than simply being an exercise in finding out information about the past for its own sake.

To illustrate, for many years I have been using a First World War recruitment poster task early in the unit - and almost every time I have been dissatisfied with it but been unable to work out why. Students generally were engaged, and seemed to find it a good task that did give them an effective understanding of WW1 at the start of their course. It was also an opportunity to get them to move around the room to study the images on the classroom walls as an alternative to sitting down at their desks. Something about it bothered me, however:

Initially, I first got students to examine who the intended audience was. Next time asked them to explore the impact of the images on the viewer. I then asked students to examine what the messages were... Etc, etc, etc. There were various iterations of all of this:The poster "Hurry up boys" is clearly directed at young men fresh out of school, while the "Young women" poster is getting women involved in recruitment. I liked the "Bovril" ad, even though many students were confused by it initially. Looking at the first version of this class task, it was clearly put in as a joke rather than as a serious source to analyse, but perhaps it is the most interesting:

Next time I will take the opportunity to explore the Empire's impact on the war too, and links in to part of the unit I am now doing on the experience of war for the soldiers of Empire (I forget where I found these, but I thought they were fascinating!):With the ideas mentioned above in mind, there is an opportunity to explore utility and perhaps reliability too; although these sources are clearly linked to recruitment, one could get students to examine the sources for usefulness for different audiences:

- A historian examining women's roles in WW1

- A historian examining the use of WW1 iconography in advertising

- A historian examining attitudes to war by ordinary people

- A historian examining war across the British Empire

The same sources to be sure, but it would enable students to get some appreciation for the role of the historian and their investigation. It might be best to limit the number of sources - less is more in this case!

The questions students would have to ask of the sources are different too. This would help them interrogate the sources, but would also help build an understanding of the nature of history. Other source investigation tasks would be useful for this too.

- What attitudes do they show?

- How does this add to our understanding of the period?

- Which sources would be most useful for the different investigations and why?

- How reliable are these sources?

- What limits their reliability?

- Does this affect their usefulness?

There are probably better ways of phrasing these, but this is a starting point I think.

Quite how I will address the issues of utility across Years 8 & 9 as a whole is something to consider next, and the ideas above will fold into it.

Thanks for reading!

Comments

Post a Comment